As Hank Ebes, founder of the Aboriginal Gallery of Dreamings (AGOD), holds a second clearance sale of works from his Cheltenham warehouse, it is hard to know whether to be saddened or elated. After all, the closing of AGOD marks the end of an era - and of an extraordinary institution. Looking through the works on the block, however, is enough to blow away those doldrums. The 353 lots in the catalogue summarize the historical emergence of the Western and Central Desert art movements and the painting cultures of the Kimberly and Top End. This post inspects a few of the works that captivate me - but don't let my choices keep you from taking your own tour of the auction lots. And as this is only the second of a series of ten projected auctions of works culled from Mr. Ebes collection, there are more treasures to come.

As Hank Ebes, founder of the Aboriginal Gallery of Dreamings (AGOD), holds a second clearance sale of works from his Cheltenham warehouse, it is hard to know whether to be saddened or elated. After all, the closing of AGOD marks the end of an era - and of an extraordinary institution. Looking through the works on the block, however, is enough to blow away those doldrums. The 353 lots in the catalogue summarize the historical emergence of the Western and Central Desert art movements and the painting cultures of the Kimberly and Top End. This post inspects a few of the works that captivate me - but don't let my choices keep you from taking your own tour of the auction lots. And as this is only the second of a series of ten projected auctions of works culled from Mr. Ebes collection, there are more treasures to come.Before perusing the paintings, though, a sketch of their collector is in order. Adrian Newstead of Coo-ee Gallery in Bondi Beach has said of Ebes: "He's the sort of bloke who makes money. He's a lone ranger; you love him or you hate him. Most people in the 'official' part of the [Aboriginal art] industry don't like him - I'm hesitant to say loathe him." To say that Ebes' backstory is unusual for a gallerist is an understatement. Born in Holland, he moved to the U.S. where, in the late-'50s, he delivered flowers and trekked through neighborhoods selling door-to-door, working illegally without a green card. With immigration authorities hot on his tail, Ebes fled to Australia in the early-'60s. After trying his hand at zinc mining and crop dusting, he made a his first killing by marketing 'Pong' to andtipodean videogamers. Using the proceeds to buy antiquarian books and prints, Ebes enraged art dealers by buying historical volumes and cutting them apart to sell the prints individually - a practice called "bookbreaking." Selling off the contents of four books by the 19th century ornithologist John Gould, Ebes generated $1.6 million from an initial $550,000 investment, completing the transactions just weeks before the 1987 stock market crash.

Casting about for another potentially profitable business during Australia's ensuing recession, Ebes began to buy contemporary Aboriginal art at a time when its primary market consisted of foreign tourists. Given the downturn in the Australian dollar, targeting buyers armed with American and European currencies made perfect business sense. Bypassing the system of indigenous community art centres put in place to ensure fair trade practices, Ebes bought directly from desert artists, undercutting competing gallerists and earning a new circle of enemies.

Within a decade, however, Ebes relationship to Aboriginal art had changed from all business to genuine appreciation. His greatest achievement in both regards came with his purchase of Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri's epic work, Warlugulong, painted in 1977. The 2 x 3.3 meter canvas is named for a site associated with Lungkata, an ancestral blue-tongued lizard and the central dreaming motif of Possum's painting. Commonwealth Bank was the original owner, having purchased the work for $1,200 in 1977. After years of neglect as an overlooked wall hanging in a training facility cafteteria, Possum's masterpiece was put up for auction without fanfare or a clue about its worth, cultural or financial. The bank expected a return of about $5,000. Art insiders knew better. Ebes leveraged several million in preparation for a protracted auction battle, but was able to purchase the work for $36,000, plus commission. It graced Ebes' living room until 2007, when a break-in in his Bourke Street gallery gave him pause. Put up for auction at Sotheby's, the work sold for $2.4 million on 24 July 2007, breaking all previous market records for indigenous Australian art. The buyer, Canberra's National Gallery of Australia, considered the work the most important in its collection.

In addition to the Aboriginal Gallery of Dreaming on Bourke Street in Melbourne, Ebes' art business generated an institution devoted to exhibiting and promoting the best of his collection. Nangara, meaning 'special place,' was the name of Ebes' collection of pivotal works - dating back to the early '70s and the origins of western desert painting - and of the exhibition that introduced Australia's indigenous art movement to new audiences in France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Denmark, Japan and the U.S. To again quote Adrian Newstead on Ebes: "He's not politically correct, but if you ask me if he's done a great job promoting Aboriginal art, I would say 'yes,' unreservedly." With the loss of his gallery lease in 2008, Ebes closed AGOD and moved his documentary and cataloguing activities to the Cheltenham warehouse, where 3,000 paintings culled from the collection await sale over the next five years. Having perused the auction catalogue of this second sale, here are some of my favorites.

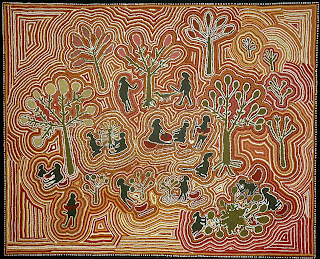

Women's Ceremony, 1989

150.5 x 122 cm.

Estimate: $3,000 - 5,000 AUD

Combining Western iconography and painting techniques associated with Western Desert art, Mbetyarre's Women's Ceremony adopts an aerial perspective to look backin time at scenes from nomadic daily life. Silhouetted women hunt, use digging sticks to collect roots, carry an elongated wood dish called a 'coolamon,' and grind seeds for roasting. Elegantly composed with a beautifully integrated palette of ochres complemented by olive green foliage, Mbetyarre's canvas conveys a nostalgic remembrance of things past.

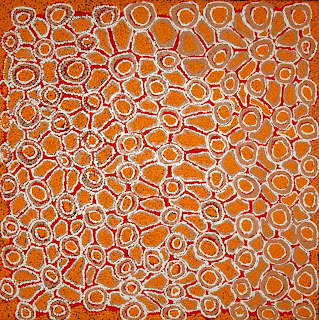

Walangkura Napanangka

Women's Dreaming at Marrapinti, 1998

91 x 91 cm.

Estimate: $3,500 - 5,500 AUD

Walangkura began painting in 1995, after working on the collaborative Minyma Tjukurrpa canvas at the historic Kintore/Haasts Bluff women's art project organized by Marina Strocci. Women's Dreaming reproduces the network pattern of roundels seen in classic Tingari Cycle paintings usually associated with male painters. Marrapinta, a rockhole site in Western Australia, is remembered in dreamings as the place a group of powerful ancestral women camped and ritually initiated younger women while traveling eastward, creating and 'opening up' country, becoming the physical features of the landscape they traversed. With its molten red and orange tones and vigorous draftsmanship, Women's Dreaming showcases the high quality of works produced for the Aboriginal-owned and operated Papunya Tula Artists group.

Maralinga, 1996

121 x 90 cm.

Estimate: $4,500 - 9,000 AUD

Jonathan Kumuntjara Brown applies the vocabulary of Western Desert art to the tragedy of Maralinga (meaning 'thunder fields), a remote area of South Australia expropriated from the Tjarutja people in the 1950s to create a nuclear testing range for British atomic warheads. While the official story was that the site was uninhabited and uninhabitable, in fact Maralinga was crossed by important 'songlines' associated with dreamings that linked desert peoples with their ancestral heritage and culture. Because the sprawling site was unfenced and inadequately patrolled, nomads wandered through contaminated territory, camping in bomb craters and trapping rabbits blinded by cobalt poisoning. Australian and British soldiers were also involuntary test subjects at Maralinga, a cold war scandal only revealed in the 1980s. Brown's painting underscores the contemporaneity of Western Desert painting and its capacity to represent living history as well as the infinite past of ancestral dreamings.

Michael Nelson Jagamarra

Michael Nelson Jagamarra

Michael Nelson Jagamarra

Michael Nelson JagamarraYam Dreaming, 2001

150 x 120 cm.

Estimate: $3,500 - 6,500 AUD

Michael Nelson Jagamarra's Yam Dreaming crackles with the jagged energy of desert life rather than Maralinga's forces of destruction. The desert yam (Ipomoea costata or 'bush potato'), harvested throughout the year, was a staple food for Aboriginal nomads throughout Central Australia. Its importance is reflected in proprietary dreamings, ritual ceremonies held to insure the plant's productivity, and paintings devoted to this vegetal spirit being and its associated sites. In this iteration of the Yam Dreaming story, Michael Nelson Jagamarra endows us with x-ray vision. A bulls-eye roundel marks the point at which the plant pulunges into the desert soil. Tuberous roots branch outward, forcing their way to the edges of the canvas. Seemingly monochromatic, the canvas upon closer inspection (click on the image for an enlargement) is flecked with a few invigorating red spatters that bring it to life.

Frog Hollow, 1995

91 x 80 cm.

Estimate: $5,500 - 8,000 AUD

Britten, a life-long stockman turned painter in retirement, was a traditional custodian of the Bungle Bungle Range, a unique landscape of horizontally banded, beehive shaped sandstone formations towering over the Ord River grasslands. Like other artists of the Warmun Art Center, Britten used locally collected natural ochres, ground into a pigment and mixed with a binding medium, to create paints that quite literally infused his canvases with local color. Britten went even farther, sometimes adding kangaroo blood to red ochres. These ritually evocative materials convey the multivalence of Britten's work, which is as layered as the sandstone landforms it portrays. His charming representation of an iconic Kimberly landscape is simultaneously an expression of gnarangani (dreaming) sagas and events.

Jack Dale

Jack Dale

Britten, a life-long stockman turned painter in retirement, was a traditional custodian of the Bungle Bungle Range, a unique landscape of horizontally banded, beehive shaped sandstone formations towering over the Ord River grasslands. Like other artists of the Warmun Art Center, Britten used locally collected natural ochres, ground into a pigment and mixed with a binding medium, to create paints that quite literally infused his canvases with local color. Britten went even farther, sometimes adding kangaroo blood to red ochres. These ritually evocative materials convey the multivalence of Britten's work, which is as layered as the sandstone landforms it portrays. His charming representation of an iconic Kimberly landscape is simultaneously an expression of gnarangani (dreaming) sagas and events.

Jack Dale

Jack DaleMap of Country, 2007

114 x 90 cm.

Estimate: $4,000 - 6,000 AUD

Like Jack Britten, Jack Dale Mengenen worked as a Kimberly stockman in a remarkable life that bridged two cultures. The son of Moderra, an Ngarinyin woman, and Jack Dale, a Scottish immigrant, Dale the younger grew up at a time when white cattlemen imprisoned and sometimes killed indigenous people for attempting to exercise their rights as traditional custodians of country transformed by pastoral use. His childhood abuse ended with his father's death, when Jack escaped to the bush. Raised and taught traditional ways by his maternal grandfather, he became respected both as a skilled stockman and an initiated tribal elder. He is a traditional custodian of Imanji, located near the Mt. House Station ranch worked by his father. Map of Country delineates the spiritual cartography of the site with terse forms rendered in natural ochres and synthetic polymers: a palette of materials as culturally hybrid as the artist's life.

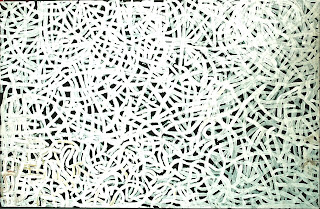

Yam Dreaming, 1995

305 x 199 cm.

Estimate: $1,100,000 - 1,400,000 AUD

Clearly the jewel in the crown for AGOD's second auction, Yam Dreaming is a sister canvas to the larger work by the same name held by the National Gallery of Victoria and featured in the Emily Kame Kngwarreye retrospective exhibition mounted by the National Gallery of Australia, which was seen from Canberra to Tokyo (where it drew more visitors than a retrospective of the work of Andy Warhol). Ebes' Yam Dreaming, like the NGV canvas, shows a filigree of white arabesques that trace the labyrinthine root pattern of the desert plant... and so much more. The artist's much quoted statement about the subject of her art was that it depicted "Whole lot, that's all, whole lot; awelye, arlatyeye, ankerrthe, ntange, dingo, ankerre, intekwe, anthwerte and kame (my dreaming, pencil yam, mountain devil lizard, grass seed, dingo, emu, small plant emu food, green bean and yam seed). That's what I paint: whole lot."

Whichever individual or institution possesses the 'whole lot' needed to purchase Yam Dreaming at auction from Hank Ebes on 18 March 2012 will surely be one of the season's hot topics among Australian art aficionados.