A traveling exhibition of works by Papunya Tula artists has just ended a successful tour of galleries in Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Berlin and Freiburg. Artkelch gallery of Freiburg organized the events, attended by over 5000 visitors. The series of shows was the first in an exhibition concept that German-Australian gallery owner Robyn Kelch calls "Pro Community." By creating an annual event that features works from a single Aboriginal art center and exhibits them a in cities across Germany, Artkelch has devised an innovative business model that supports the gallery's mission "to inform and enlighten (Europeans) about the culture and conditions of Aboriginals in Australia's recent history." This is especially important in Germany, Switzerland and Austria, where contemporary Western Desert art has begun to open eyes and minds, but still "is often categorized as indigenous folk art or handicraft," according to Kelch. In the service of both collectors and artists Artklech promotes knowledge about ethical practices of artistic production and distribution - in other words, a model enterprise.

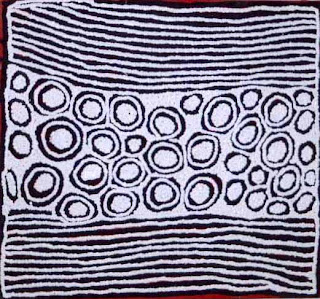

A traveling exhibition of works by Papunya Tula artists has just ended a successful tour of galleries in Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Berlin and Freiburg. Artkelch gallery of Freiburg organized the events, attended by over 5000 visitors. The series of shows was the first in an exhibition concept that German-Australian gallery owner Robyn Kelch calls "Pro Community." By creating an annual event that features works from a single Aboriginal art center and exhibits them a in cities across Germany, Artkelch has devised an innovative business model that supports the gallery's mission "to inform and enlighten (Europeans) about the culture and conditions of Aboriginals in Australia's recent history." This is especially important in Germany, Switzerland and Austria, where contemporary Western Desert art has begun to open eyes and minds, but still "is often categorized as indigenous folk art or handicraft," according to Kelch. In the service of both collectors and artists Artklech promotes knowledge about ethical practices of artistic production and distribution - in other words, a model enterprise. Among the outstanding works displayed (and, for the most part, sold) during Papunya Tula's storming of Germany, the most memorable for me is one by Tjunkiya Napaltjarri (shown). A remarkable innovator, she abandoned the conventional western desert dotting technique for one in which the acrylic paint was instead pushed across the canvas in nervous, jagged strokes. When combined with bold graphics, her signature technique gave canvases a raw, almost feral edginess. The piece unveiled posthumously in Frankfurt opening is singular, integrating the linear and concentric motifs that alternated in her late work. Its harmonious composition exudes confidence and joy - and it comes as no surprise that the piece, which feels like the culminating work of her late career, sold on opening night.

Of course, the opening at Berlin's Artbar 71, co-sponsored by the Australian embassy, proved why the city got its postwar reputation as a breath of fresh air in nose-to-the-grindstone Germany. I wonder where the patron with the leather gear was headed after the opening. On the other hand, some things probably are better left unasked....