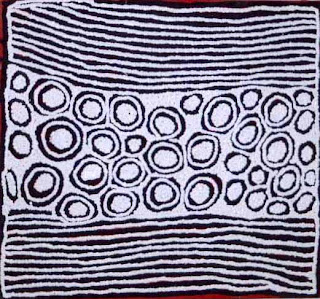

The similarities between the Wandjina by

Lily Karada, left, and the painting of an Ancient King by the self-taught African-American artist

Richard Burnside, right, are more than merely superficial. Karada's Wandjina is a figure from the dreamtime and is ritually painted at ancient sites by Mowanjum people to ensure the cyclical arrival of monsoon rains. Burnside paints kings in a ritual allowing him to "find relief" from "night visions of ancient times." Beyond this coincidental overlapping of collective and personal dreamings, both works can be seen as "outsider art," at least as the term is defined by Colin Rhodes, a professor of art history and theory at the University of Sydney and author of

Outsider Art: Spontaneous Alternatives.

"The artist outsiders," Rhodes writes, "are, by definition, fundamentally different to their audience, often thought of being dysfunctional in respect to the parameters of normality set by the dominant culture. What this means specifically is, of course, subject to changes dictated by history and geographical location." Burnside's unschooled technique, production of images to exorcise unwanted spiritual companions, and marginal status within the dominant American society qualifies him as an "outsider" artist on multiple levels. Aboriginal peoples can also be seen as outsiders, given "a post-colonial situation in which the colonizer has become 'naturalized' and speaks with the dominant cultural voice." Contemporary Aboriginal art, ranging from Western Desert works representing indigenous dreamings using non-traditional media to works "that reveal Australian history as seen from the Aboriginal perspective, from pre-European life to politically charged images of institutionalized racism," all qualify as creative artifacts of an outsider perspective, as Rhodes defines it.

The exhibit of works by Billy Benn Perrurle,

To Paint Every Hill at NG Art Galley in Chippendale (Sydney), showcases the signature landscapes of the most celebrated Aboriginal outsider artist. Born in 1943 in Artetyerre (Harts Range), he labored from childhood in mica mines and later became a drover. In 1967, Perrurle shot and killed a man, and for the next two weeks evaded the police, shooting and wounding two officers. Acquitted by reason of insanity, he ended up in Alice Springs, eventually working in the sheet metal shop of the Bindi Centre, a service provider for the developmentally disabled. He began painting on discarded pieces of plastic and plywood in a corner of the shop around 1980, depicting his mother's and grandfather's country with delicate, intricate brushstrokes. These small landscapes, unschooled in technique and created out personal need rather than for financial gain, conform to the understood criteria of outsider art.

Discovered by the mainstream art market at the 2000 Desert Mob exhibition, Perrurle has since become a major figure with works acquired by the National Gallery of Australia, The Art Gallery of New South Wales and the National Gallery of Victoria. As the 2006 winner of the coveted Alice Prize, where a plaque beside his premiated work announced: "He wants to paint every hill from his country and then he will stop, then he will return home," Perrurle has well and truly arrived.

Perrurle's painting

Harts Range/Alice Range in the NGA collection (above), created around 1997, depicts his birthplace from memory. Its representational language is both familiar and strange. Hills rise in oleaginous swirls toward a sky that is blue, yet ominously dark. An incongruously bright stand of trees leaps from the foreground, then dissolves into the murky distance.

As an Aboriginal landscape painting executed in non-traditional media and iconography, it poses the same intriguing questions raised by the watercolors of Albert Namatjira - and indeed, Perrurle admires Namatjira as a "great painter." As noted by Alison French in the excellent exhibition catalogue

Seeing the Centre, Namatjira may have employed techniques and an iconography shared with non-Aboriginals, but his relationship to the landscape he painted remained proprietary and inaccessible. He almost never spoke of his 'Dreaming place,' but his works mapped it in ways ignored by collectors. Arnhem Land painter Galarrwuy Yunupingu maintains that "

he was painting his country, the land of the Arrernte people.... No one asked him the name of the name of the country he was painting, or the Dreamings that made that country important.... The buyers did not recognize the Aboriginal law which bound him to the land that he painted." Perrurle's paintings appeal to a broader group of collectors than more "orthodox" Western Desert art, with its iconography of dotted roundels and arcane symbols. Yunupingu warns us that, in terms of fundamental meaning, Perrurle's works may be equally inscrutable; their readings as realist representation merely the product of a deluded eye and a lazy mind.

Perrurle's work changed a few years ago after he revisited the country of his birth, the site of the tumultuous events of his early life. Brushstrokes gained gestural strength, his color palette brightened, mountain profiles took on a vivid, mannerist grandeur. Perrurle's landscapes seem to have emerged from the haze of memory into an insistent, almost hallucinogenic presence. The speed at which he paints has also increased. A cynic might explain this as reality of a hungry market for his paintings making itself felt: a common trajectory in the 'post discovery' career of American outsider artists like

Jimmy Lee Sudduth. But another explanation for this outpouring of landscape visions is also likely, as noted in the caption of Perrurle's Alice Prize-winning painting: "

He wants to paint every hill from his country and then he will stop, then he will return home." Perrurle's iconic fragments of country may be the products of a idiosyncratic ritual still in flux, the evocative byproducts of an outsider's personal dreaming.

-Gugaman_196-09_web.jpg)